Some Captured History of Glanamman and GarnantThe Tinplate Industry at CwmammanSteel is iron with a percentage of carbon added to it in order to "harden" it. Iron and steel are vulnerable to rusting, when oxygen and moisture react with the iron to form "iron oxide". This natural reaction can be prevented by coating the iron or steel with some other substance so that it is not exposed to the oxygen in the atmosphere. Even today, tin is used to cover the steel used in tin cans, and the process of covering iron or steel with tin is called "Tinplating". It is important to remember, however, that the steel in the can is only protected when the layer of tin is unbroken, so be wary of eating food from a dented tin! Since the early 19th century, the manufacture of tin cans for food preservation meant a demand for tinplate. Household utensils were also made from the product and the availability of the raw materials needed to produce tinplate meant that Cwmamman was well suited, at least in the 19th century, for the manufacturing of the product. The Amman Tinworks at Garnant was built in 1882 and started operations in 1883. It was sited by the side of the River Amman at what is now "Golwg-yr-Amman Park" and the foundation stone is still visible in the vicinity of the Memorial Stone. An inscription on the foundation stone states that it was laid by Rev. Griffiths, Vicar of Christchurch in May 1882.

Location of the Foundation Stone at Parc Golwg yr Amman.

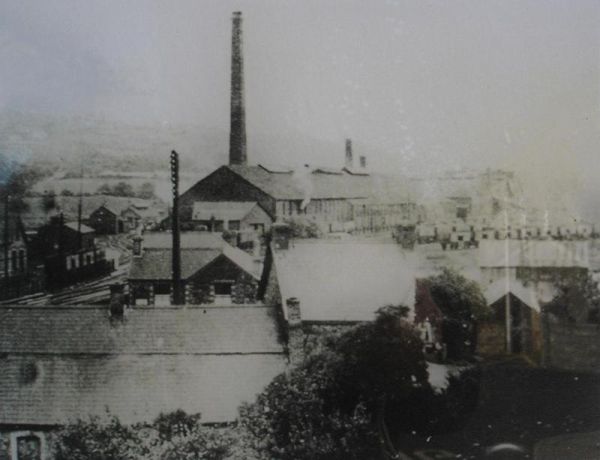

The Foundation Stone of Amman Tinplate Works. The 1895 edition of Kelly's Directory listed "Garnant Tin Plate Co. Limited (The)", with a gentleman named John Thomas shown as the proprietor. The 1910 edition listed "Amman Valley Tinplate Co" with Gwilym Rees as the manager. The Amman Tinplate Company are believed to have employed around 120 men and women at the works. At the time of opening, there was a great world wide demand for Welsh tinplate, with 75% of the total amount produced being exported to the USA. An import tax known as "The Mckinley Tariff" imposed on imports into the USA in 1891 had serious implications for the Welsh tinplate industry. The First World War also created problems due to a shortage of essential coal. The inefficiency of our pack mills meant that the Welsh tinplate companies could not compete with the more modern and efficient system of the strip mills built in the USA. The Amman Valley Chronicle reported in it's 24th July 1913 edition, that there was the risk of a stoppage at the Garnant Tinplate Works due to the depression in the industry. The workers had been given notices, which had expired on the previous Saturday, but work had continued on a day by day arrangement. There was also a rumour circulating that if any stoppage did occur, the works would be idle for an indefinate period, causing a great loss to the locality due to the large number of workmen employed there. On the 16th of July, 1913, there was a conference at Swansea of the leaders of the Steel Smelters, Tin and Sheet Millmen, Dockers, and Gasworkers' Unions. Because of the poor condition of the industry, they passed the following resolution: "Realising the serious condition of trade, we are of opinion that a stoppage should take place of all the tinplate mills and tinhouses in the first week in September, and consider that such would be of advantage to the trade generally; but before taking the action of presenting notices in the first week in August, in order to bring such stoppage about, we decide to submit the question to a ballot vote of the members of the various societies for their decision." A circular was drawn up with an explanation to the union members for the union's decision: "As you are aware the employers are divided among themselves, although the majority of them are in favour of periodical stoppages. When the employers fail to agree among themselves it is impossible to bring about a general stoppage, and we are therefore of the opinion that the only way to bring about an effective stoppage is for the men to take the matter in their own hands. The trade is in a deplorable state. About 25 per cent of the men have been idle for months, and some families are in distress. The ultimate results will be that reductions will creep into the trade because the men will be compelled to do something to relieve the distress among the wives and children. Once these reductions creep in they will spread like wild-fire all over the trade. We do not want to go back to the old chaotic conditions prevailing previous to the establishment of the Conciliation Board; therefore it is up to the tinplaters to save the situation. We suggest that notices shold be handed in on the first Monday in August with a view of bringing about a week's stoppage on the first week in September." 22,000 papers were sent out asking "Yes" or "No", as to whether the tinplate workers were in favour of the stoppage. The exact figures were not disclosed, but there was not enough support from the workmen for the planned industrial action. There was therefore only the usual stop-week in August. The 4th of September 1913, edition of the Amman Valley Chronicle reported that the recent "stop week" had brought about a reduction in the stocks at Swansea Dock warehouses. We also learn from the same article that despite prices in the tinplate trade remaining low, there were signs that the depression in the industry were becoming much less acute. Recently, a fair percentage of the mills that were idle had restarted and there had been no recurrence of trouble on the continent. There had been a helpful reduction in the price of steel bars and block tin and some of the works were still able to produce tinplates at a fair profit, though a real revival of the trade depended on better prices being obtained. Despite the careful optimism for the South Wales tinplate industry in general, the A. V. Chronicle on the 18th of December 1913, reported that Garnant Tinplate Works had been idle for the week and that the outlook for a re-start was bleak. On the 19th of February 1914, the Chronicle continued to report on the industrial gloom for Cwmamman's miners and tinworkers. There were at that time, many empty houses in Cwmamman due to the fact that several families had moved away. There were also others who were thinking of leaving the area in order to find work. There was a serious fire at the Glanamman Raven Tinplate Works in the early hours of Thursday the 27th of June 1916. A crowd of people gathered and workmen did their best to get the fire under control. The following weeks edition of the A.V. Chronicle reported on the events and special mention was made of Rhys Roberts the engine driver, who was given credit for saving the engine by using a hose pipe, while "pantiles and burning timbers were falling all around him". The Swansea Fire Brigade were at the scene within three quarters of an hour after they were alerted and managed to put the fire out. A section of roof above the main engine, spanning 15 yards (Metres), was destroyed. Despite the fact that the engine did not suffer extensive damage, the cost of the fire was estimated to be about £1,500 and four mills were unable to be used until the following Monday. The roof was repaired by John and Owen Evans, contractors from Glanamman. An unusual accident happened at the Raven works on Tuesday the 29th of April 1924, when a leather belt on the engine snapped and caught a piston rod, which in turn caught the boiler. The top part of the boiler which weighted approximately a ton, was sent skyward and landed on the wooden staging which was fixed around the engine. Two men; a Mr Hughes and a Mr Rees had a very lucky escape as only a second earlier, they were working right under where the boiler top landed. It was such a near miss that the two had part of their clothing pinned down under the weight of the metal part. Although the galvanising part of the tinplate works was not affected, the extent of the damage meant that two boilers had to be replaced and a large number of men were left without work while the repairs were carried out. It was expected to take about four or five weeks before that part of the works was able to reopen. The Amman Tinplate works was idle for over 16 weeks in the Summer of 1927, with work resuming on the 29th of August. A breakage of machinery was the cause of a stoppage at the Amman Tinplate Works at Garnant in June of 1929. Work did not resume until Monday the 19th of August after an idle period of approximately eight weeks. Amman Tinplate Works At some point, the Amman Tinplate Works were taken over by Jones Brothers, who were in turn later taken over by Richard Thomas and Co. who closed the Amman Tinplate Works permanantly around 1932. The 1923 edition of Kelly's Directory listed the Amman Tinplate Works as part of "Grovesend Steel & Tinplate Co. Ltd" with John A. Bracey as the manager. At a meeting of the Cwmamman Urban Council on the 31st of December 1935, the Clerk (Mr G. Tracy Phillips), reported that he and two other members had interviewed Mr T. O. Padbury and Mr Rees, who were directors at the Grovesend Steel Works. Mr Padbury stated that there was at that time no hope of either the Amman or Raven Tinplate Works reopening, due to the state of the foreign market. The councillors asked whether the tinplate works could be converted to any other purpose but were told that nothing could be done at the present time. The problem of the loss of foreign markets was highlighted by Sir William Firth, head of the Richard Thomas and Co tinplate combine, in his speech at the Amman Valley Hospital opening ceremony, when he was asked to explain why the Raven Tinplate Works (at Glanamman), were idle, in June 1936. Sir William Firth The Raven Tinplate Works were sited at Glanamman and today the location is used as a council depot, where the refuse collection lorries are kept. The name "Raven" is often associated with land that was part of the Dynevor estate and the Raven Tinplate works are sometimes mistaken for the Amman Tinplate Works at Garnant (even on a local authority tourism leaflet). To complicate matters further, the name "Raven Tinplate Works" may have been a misnomer, as it is believed that the works didn't actually produce tinplate. Sir William Firth stated in 1936 that the Raven works were engaged in the manufacture of thin gauge black sheets and thin gauge galvanised sheets. He explained that he and Henry Folland were unable to keep the works open, as for the three or four years before the Raven Tinplate Works closed, every ton that was produced there was sold at a definite loss. Raven Tinplate Works When the Raven Tinplate Works were operating, the entire output, 24,000 tons, was exported to Japan, which also imported 140,000 tons from England with the rest of its requirement coming from America. Sir William Firth explained to the crowd in June 1936, that Japan now not only met her own requirements but also exported her products to Rangoon (Burma) and to India. There was therefore, no market for the goods made at the Raven Works. He stressed that unless a strip mill was built in the country, he feared that the whole of the British Tinplate Industry would not be able to compete with countries like Japan, India, Russia and Germany. He urged the men in the crowd to get together to build one. According to information on a local authority tourist information board, the Raven Tinplate Works opened in 1881 and old maps of Cwmamman dated 1878, show that the location was once the site of the Cwmamman Brickworks. Other informal sources suggest that the Raven Tinplate Works closed down in 1930. By 1937, Sir William Firth had announced that Richard Thomas and Co were to build a new strip mill at Irthingborough, Northampton. The location was chosen because of the iron ores available in the area. It was bad news for the Welsh economy and for the furnaces who supplied the steel bars for the tinplate works. A cross party of Welsh M.P.'s met with the prime minister, Stanley Baldwin (who was the son of Alfred Baldwin the Ironfounder and Tinplate manufacturer) and the ultimate result of this meeting was that the new strip mill was erected at Ebbw Vale. Richard Thomas and Co merged with Baldwin's in 1948 to become Richard Thomas and Baldwins Ltd. The Raven Tinworks were demolished sometime after 1949

and a photograph of the derelict buildings taken at that date is held

at the National Museum of Wales at Aberystwyth. There is now also no

trace of the water feeder pipes which crossed Folland Road, Glan-yr-afon

fields and the River Amman, near Aber Fflach which served the Tinworks. How the Amman Tinplate Works operated.The works consisted of three departments, the largest of which was made up of the hotmills, coldrolls, annealing furnace and pickling plant. The second department consisted of the washing pots. The third department was a small building for the sorting and boxing plants. Opposite the main building, there was a shed where the used pickling acids were converted into copperas for other uses. Iron bars were heated until they were glowing hot and then fed through a set of rollers which were powered by a steam engine. The flattened iron bars were fed through the adjustable rollers on several occasions, until they became thin sheets; each time the metal was fed through the rollers, they became thinner and longer. Once these "Blackplates" had been worked to the correct dimensions, they were dipped into baths of diluted hot sulfuric acid at the pickling plant, in order to remove any oxidisation. After being washed in water, they were placed in an oven known as an "Annealing Furnace" for several hours, then removed and left to cool. After cooling, the blackplates went through coldrolls to remove any unevenness before they were returned once again to the annealing furnace. After a further treatment at the pickling plant, the washed blackplates were stored in slightly acidic water until they were ready to be used. This was to stop any oxidisation of the treated metal before it was coated with the tin. The blackplate was dipped into a bath of molten (melted) tin, with flux floating on the top. As the plate was lowered into the bath, the flux would help the tin to stick to the blackplate. The blackplate was then lowered into another bath, which contained molten tin at a lower temperature. Further treatment of the blackplate by dipping it into a bath containing a type of oil, would help to remove any excess tin. After being cleaned and polished, the tinplated sheets, each with the dimensions of 14 inches by 20 inches (35.5cm x 50.8cm), were packed in boxes of 112 sheets. Each box weighed approximately a hundredweight (50.8kg). Further information on the Welsh Tinplate Industry can be found at the Kidwely Industrial Museum Website. Information on this page was taken from the Amman Valley Chronicle, the Wikipedia website and a series of newspaper cuttings from an unknown source (author unknown). Thanks also to Huw Walters for his contribution.

|